Originally presented for HIST 4080.001, Dr. Laura Stern, April 14, 1999

Discussing the social environment of the past is proving to be an interesting challenge to all historians, especially those who view it with a modern perspective. The past should be acknowledged as alien to us, and to understand its complexities one must learn to think like an ancient and use their value system to determine right or wrong. Modern-day attitudes towards homosexual behavior are strong and opinionated, a far cry from the environment found in medieval England between the 11th and 13th centuries. In that time, many could argue that such debate was not mainstream and that life was good for those who loved the same sex, whether in the secular or religious worlds. This attitude can be found across the continent and it proved to be strong and healthy in England, which always enjoyed a degree of independence from the Church in Rome. Was sodomy a concern for the medieval Englishman? If not, what caused attitudes to evolve into their modern form? To discuss England’s hospitable environment, reasons for persecution must be discussed as well as how same-sex affection was expressed.

It is useful to briefly discuss the reasons for Christian society to outlaw homosexual behavior and to discover where such references to ancient law originated. Important to note is the term homosexuality, which is a 19th century invention. In medieval times, no such word was used; instead, practicioners of same-sex love were grouped together by scholars with other deviants such as masturbators, fornicators, and molestors of both children and animals. All together, they were called “Sodomites,” a reference interperting them as inhabitants of the city of Sodom and possessing their special sin. What makes Sodom’s sin so exceptional is the punished meted out by God: a rain of fire and brimstone intent on wiping out all evidence of sin, producing a desolation that remains to this day as a reminder of God’s justice.[1] Modern scholars generally concur that the lesson learned from God’s exceptional punishment of the city of Sodom is not one that preaches against same-sex relations, but against inhospitality. Providing shelter in the ancient world was considered an obligation amongst the people of the Middle East, for there were a lack of inns and other shelters in the harsh geography of the eastern Mediterranean.[2] Indifference can be seen by the number of the early Christians, some of whom were canonized, who continued to practice same-sex love even after learning this tale.[3] For the purposes of this paper the word homosexuality will be used to describe the wealth of passionate acts associated with same-sex love, but it must be stressed that the harsher term of sodomy was the popular way in medieval times to address a most heineous sin.

In England, persecution against homosexual behavior was greatly hindered by the attitude towards it taken by the English bishops. English bishops descend from a Anglo-Saxon background, where homosexuality had existed far longer than the Catholic Church. Indeed, few references against homosexuality exist in English law-codes, perhaps indicating an indifference to it amongst the authorities. A Catholic belief is that the entrance to Heaven can only be granted by divine authority.[4] Sacraments, the tools needed to gain this salvation, were held by the Church and employed by the bishops. Already, bishops possessed strong divine powers, including the power to forgive certain sins.[5] Concerning clerical sins, accepted punishments for sodomy involved different levels of penance, ranging from one to ten years on average depending on the act performed.[6] Most of the English bishops were content to employ such traditional punishments because of their desire to reform the sinners and continue to keep them in the Church. The Church always protects its own, and once the offender completed their penance he was reinserted into their former positions. Every holy man spends his life attempting to control his desires, and the Pope advocated humane treatment of those who slipped in their duties.

Practices as ingrained as these are near-impossible to eradicate, especially when using just church decrees and papal edicts.

There has always been a pastoral concern for homosexual behavior within the ranks of the clergy, but little material exists that describes stance of the general populace towards or against it.[7] Accusations of sodomy are evident in the chronicler’s histories of the Norman kings and reflect native resistance to their new rulers. Sodomy was just one of the many scandals associated with the conquorers, a long list of sins serious and silly that include removing holy days from the calendar to possessing effeminate haircuts.[8] Archbishop Anselm was known to accuse the Normans of sodomy, and his frustration from being appointed to the Diocese of Canterbury against his will was obvious in other affairs. The chroniclers even went so far as to attribue the drowning at sea of Henry I’s sons William and Richard (along with three hundred others) as God’s just punishment for the royal party’s sexual immorality. An inportant event that many of the chroniclers fail to note is that William was originally safe but drowned after returning to save his sister Mathilda. The bitterness of the conquored taints their histories, and therefore the chroniclers cannot be completely relied upon for truthful insight.

English literature possesses a distinctiveness that illustrates the isle’s separation from the continent. The vivid sources of Sts. Anselm and Aelred give colorful insights into monastic life and the emotions they expressed and struggled with. Both were involved in the national debate concerning sodomy, but neither figure showed interest in actually rooting out the practice.[9] John Boswell provides passionate excerpts of the epistles that Anselm, then abbot of Bec, addressed to his brethern. Take this example, a letter by the abbot addressed to a friend:

“Brother Anselm to Dom Gilbert, brother, friend, beloved lover…sweet to me, sweetest friend, are the gifts of your sweetness, but they cannot begin to console my desolate heart for its want of your love…Not having experienced your absense, I did not realize how sweet it was to be with you and how bitter to be without you.”.[10]

As can be seen, this relationship shows Anselm’s capability for the profound expression of affection, which is not an isolated incident in Church circles. Boswell also writes of Aelred, abbot of Rievaulx, as a major figure in the expression of same-sex love in a Christian context:

It was Aelred who specifically posited friendship and human love as the basis of monastic life as well as a means of approaching divine love.[11]

The examples of Anselm and Aelred show the emotional aspect of same-sex love that came to be widely practiced and celebrated by the English clergy.[12] The latter was known for indulging himself in casual physical encounters, but the love he felt capable to express was for God alone. Aelred would use the discipline of his vows to overcome his sexual urges, perhaps providing an example for the monks in his care on how to properly express their strong feelings for one another.

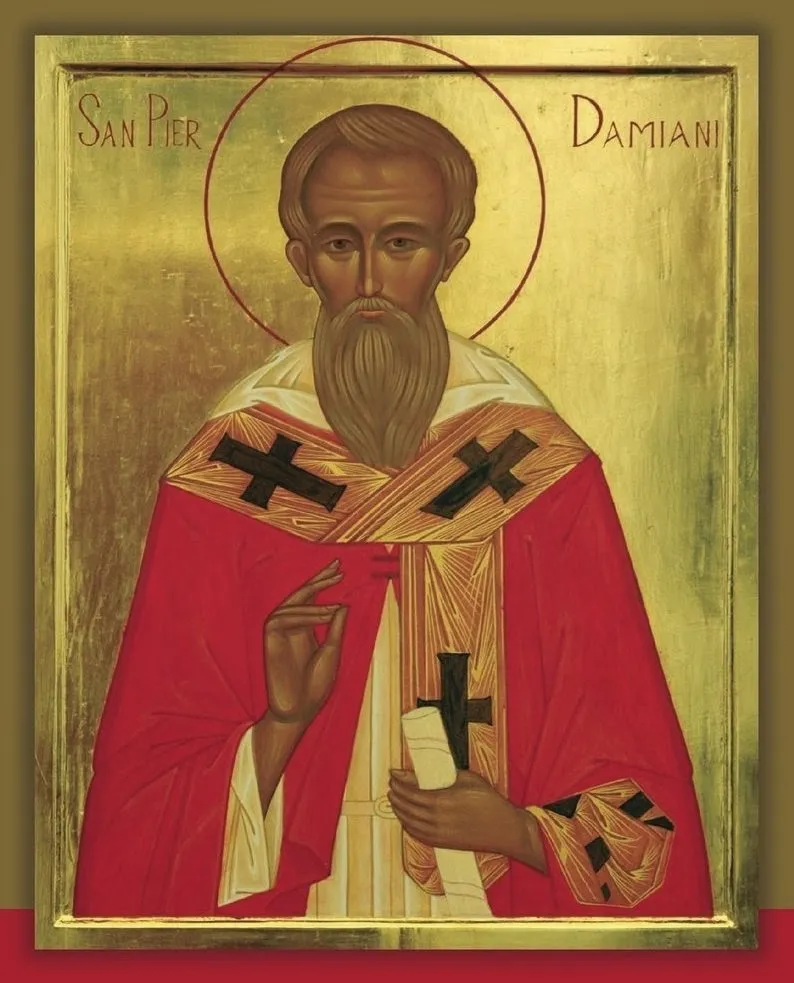

Beginning in the mid-11th century, the papacy in Rome began a sweeping reform that sought to regulate many social institutions. The effects of this movement seem mixed in regards to same-sex love. The struggle to eradicate sodomy was an important issue for the Church to tackle, since it was side note to the reorganization of marriage in both the laity and clergy. The Urban reformers of this time saw the abolition of clerical marriage (and the sexual relations it brings) as one of their foremost goals. If force was required to do this, so be it.[13] An important figure in the early stages of this reform was Peter Damian, an Italian monk and author who was zealous in his anti-homosexual opinions. His open letter was Book of Gomorrah, a monograph written c. 1049 for Leo IX’s consideration and addressed to those who practice sodomy. The book is exceptional for being the earliest example of a greviance concerned with ridding the Church of sodomy. Opinions differ on the motivation for Damian’s authorship, but most suthorities speak of his attenance at the Council of Reims in 1049 and the supression of his concerns about homosexuality in the Church.[14] Damian not only took issue with clerical sodomy, but also with other deviant practices including mutual masturbation and lover’s confessing to one another, both of which are attempts to absolve freshly-committed sins (the blind leading the blind). To Damian, Church authorities sanctioned this behavior by not taking as strong of a stance against it as he was. Perscribing penance was not effective enough in removing this scandal. Damian advocated severe punishments and was zealous in his belief that defrocked priests must never be allowed to return to the Church.[15] Damian wrote in a fanatical tone, hoping to persuade the Pope that reform had to be initiated. Unfortunately, the papacy newly-elected and indifferent to Damian’s book, which was subsequently shelved and ignored.[16] The Book of Gomorrah’s publication had little effect in England before or after the Norman invasion, since all English reform was traditionally directed from Rome.

The first prohibition against homosexuality occurs in 1102 at the Council of London.

It would be over 150 years before serious action on these issues was taken by the Pope, Innocent III.

These historical records show that in medieval times homosexuality was seems as a learned behavior alien to England, capable of being transmitted from one area to another. Logic would tell the modern reader that it is not possible for England, or any place, to have been a natural, sexually neutral paradise that had not already incorporated sodomy into its practices; the public then was not as aware as it is today.

Footnotes

[1] Jordan, Mark D. The Invention of Sodomy in Christian Theology. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 32. “(Sodom) is a memorial site that records God’s power to judge…a most articulate reminder of the consequences of rebelling against God. We remember (it) because we need to learn obedience from it.” On p.101 Jordan also relates Sodom’s punishment to their rejection of “God’s gift of a sexed body,” so made for the singular purpose of procreating with a member of the opposite sex.

[2] This could mean that when the inhabitants of Sodom press Lot to bring himself forth so that they might know him, they were questioning his practices as a foreigner. Two words used by the Greeks for “to know” are similar, but one has a social meaning, the other a sexual. It would have been very easy for one scholar to misinterpert the word and hence taint any translations.

[3] John Boswell. Chritstianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), p. 135. Perhaps this attitude arises from the early Christian emphasis on love, and that quest for divine love can be explored through same-sex love.

[4] John 10:7.

[5] Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People. (London: Penguin Books), 90-1. Bede provides the precedent of Augustine, the first Archbishop of Canterbury, who was granted the ability by Pope Gregory in 601 to establish bishoprics and appoint their rulers. This was done to help ease the distance between Canterbury and Rome and assist the conversion of England. Often the English clergy have been given special powers that the Pope might possess exclusively in other areas of the continent.

[6] Brundage, James A. Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), p. 600. Bede advocated at least a year for beastiality and four years for anal sex. Burchard of Worms provides examples of extreme penances, but those were mostly concerned with limiting adultery and deviant sexual behavior like beastiality and oral sex. This author could find no reason for the omission of punishments for anal sex, it is known that Burchard imposed harsh penalities for fornication because of the fact penetration was involved.

[7] This dichotomy makes perfect sense. After all, the clergy in early England and elsewhere were the literate class, the ones that had the ability to produce the histories read today. Their records more often than not are concerned with the Church’s particular brand of politics.

[8] Frantze 243 and Boswell 229. Interesting to note is that homosexuality was considered by some to be an Arab vice, which Robert of Normandy perhaps imported upon his return from the Crusades.

[9] Boswell 216. An interesting coincidence is that Pope Alexander II and St. Anselm were both pupils of Lanfranc, perhaps explaining their similar disinterest in rooting out sodomy.

[10] Boswell 219.

[11] Boswell 222.

[12] Boswell 224. “Aelred stressed that friendships could not simply be intellectual. ‘Feelings,’ he observed, ‘are not ours to command.'” Aelred also believed that carnal relationships produce a lover’s joy, a powerful stepping stone to a greater relationship between the lovers and God.

[13] Brundage 183.

[14] Brundage 215. Brundage talks about Damian’s crusade against clerical marriage and links that interest with his widely-known “deeply-rooted…personal horror of sex.” As previously evidenced, clerical marriage and sodomy were practices linked together in the eyes of the reformers, the elmination of one necessitating the eradication of ther other.

[15] Damian, Peter. Book of Gomorrah. trans. Pierre J. Payer. (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press), 35. “(If) an unclean man has no inheritance at all in heaven, by what rash price should be continue to possess a dignity in the Church which is no less the Kingdom of God?”

[16] Boswell 213. Interestingly enough, Pope Alexander II, an important reformer in his own right, was so annoyed with Damian’s persistence on eradicating gay sexuality that he actually stole his lone copy of Book of Gomorrah and kept it locked away. See the note below concerning Alexander’s link to Anselm.

Member discussion