Today I read a tweet about Volvos, which made me think of the only friend I’ve ever known to actually drive a Volvo (Katie Thomas). From there, I started…

Officer Cueball, Southlake P.D.

Today I read a tweet about Volvos, which made me think of the only friend I’ve ever known to actually drive a Volvo (Katie Thomas). From there, I started…

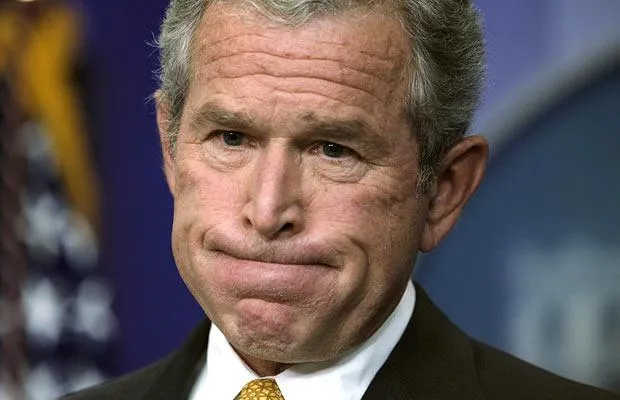

It’s nearly 13 years later, and George W. Bush still sucks. But the night of his election was still one of my funnest memories. That evening, Micha and I…

Twelve years ago, I went to Houston to see my brother Michael. While I was helping him with some yardwork, I found his old DirecTV system sitting in the garage.…

[11:39] Jenn: I just realized how if I didn’t know you I would have nothing to do for the next 4 days [11:39] Jenn: today – soccer game…

Awhile back, I waxed poetically about the manna from heaven that is Cane’s Sauce. This was picked up by the Raising Cane’s Twitter account, and I was later…

Chris, Christina, my girlfriend Ellen and I walked into Campisi’s. None of us had ever been to this restaurant before. After years of hearing how great it was, we…